To live on the northern shores of Lake Michigan is to frequently confront the ancient past — whether in the form of Petoskey stones, or the glacial topography of dunes, moraines, erratic boulders, and kettle bogs.

As a kid, I vacationed with my family on the Atlantic, where life is teeming. Swimming in the salty waves, you might feel an unseen creature brush against your leg. You might dodge a horseshoe crab, or witness an angler catch a shark simply by casting into the surf. There’s so much — a mind-boggling, infinite amount — of life in saltwater. It’s life, life, life, everywhere. You can smell it.

So when I moved up north, to the coast of a freshwater inland sea, I was struck by the ancientness, the quiet, the peace. Walking on a beach in Leelanau, you won’t find seaweed or sharks, but you’ll find fossils in the sand. You’ll find things from a long time ago. If you go swimming in Lake Michigan, you’ll feel liberated by the relative paucity of life in those waters, as though you have the whole giant lake to yourself. And your own life will seem to loom large against the absence of life. You’re a human, a glorified ape, swimming in a boundless placid pool. And you’ll think “Some day the Atlantic will be like this. Someday everything will be like this: fossilized. And we’ll all be gazing back into the past.”

So when I moved up north, to the coast of a freshwater inland sea, I was struck by the ancientness, the quiet, the peace. Walking on a beach in Leelanau, you won’t find seaweed or sharks, but you’ll find fossils in the sand. You’ll find things from a long time ago. If you go swimming in Lake Michigan, you’ll feel liberated by the relative paucity of life in those waters, as though you have the whole giant lake to yourself. And your own life will seem to loom large against the absence of life. You’re a human, a glorified ape, swimming in a boundless placid pool. And you’ll think “Some day the Atlantic will be like this. Someday everything will be like this: fossilized. And we’ll all be gazing back into the past.”

These thoughts were the backdrop against which I first experienced the Kettles Trail, a new trail within the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore which brings you face-to-face with the glacial legacy of our area.

Let’s talk about what a “kettle” is.

The website Geocoaching explains: “Kettles are depression landforms that are created by a receding glacier. Many kettles are partially or wholly buried by glacial outwash when streams of meltwater carry sediments that form a broad outwash plain. When ice blocks fall away from the receding glacier and melt, a kettle hole is left behind.”

The website Geocoaching explains: “Kettles are depression landforms that are created by a receding glacier. Many kettles are partially or wholly buried by glacial outwash when streams of meltwater carry sediments that form a broad outwash plain. When ice blocks fall away from the receding glacier and melt, a kettle hole is left behind.”

These ancient melting ice blocks formed crater-like holes in the landscape, which turned into ponds and bogs that became choice environments for spring wildflowers and other specialized flora and fauna.

Imagine a bowl. And imagine that you’re walking around the rim of the bowl. And at the bottom is the bog or pond. That’s the experience of hiking the Kettles Trail and seeing these unique “depressions.”

I almost skipped the hike that day. I had obligations in the morning and the late-afternoon. But I’d been wanting to experience this new trail — created by the Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, in conjunction with the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore — for a while. So I forced myself out into the outdoors. Which is almost always a good idea.

And it so happened that the clouds parted when my car entered the parking lot off Baatz Road, and sunshine lit up the winter landscape. I even had to put on sunglasses to combat the glare. That vitamin D! In February, it’s a precious commodity.

And it so happened that the clouds parted when my car entered the parking lot off Baatz Road, and sunshine lit up the winter landscape. I even had to put on sunglasses to combat the glare. That vitamin D! In February, it’s a precious commodity.

Initially, I thought big boots would suffice. But as I started hiking, I realized the snow was deeper than I thought. And then I was really glad that I had purchased snowshoes this winter, and that I always kept them in my car. So I decided to double back to the parking lot and change my footwear. It was the right decision. Snowshoes and poles were absolutely necessary to navigate the terrain that lay ahead of me.

The Kettles Trail is not an easy one, in winter. Though the first part of it is, notably, handicap-accessible when there’s no snow, it’s definitely not handicap-accessible in winter. Suit-up, gear-up, and get ready, because you’ll be trekking through a fairly difficult trail in the snow.

There aren’t any trail markers (rectangles of bright paint on trees) that I could see. So you’re reliant on tracks of other hikers and cross-country skiers. But windy sections of the trail — sections which were bitterly cold; I’m glad I always bring my scarf, even when I don’t think I’ll need it — can almost completely erase tracks. This meant that I missed the early “Overlook” of a kettle on the trail. I saw the sign for it, but I didn’t see tracks or even hints of tracks, and I wasn’t willing to veer off course and risk getting lost in the woods. But that was ok. For every trail you experience for the first time, it’s nice to leave at least one thing undiscovered, as an incentive to go back soon.

There aren’t any trail markers (rectangles of bright paint on trees) that I could see. So you’re reliant on tracks of other hikers and cross-country skiers. But windy sections of the trail — sections which were bitterly cold; I’m glad I always bring my scarf, even when I don’t think I’ll need it — can almost completely erase tracks. This meant that I missed the early “Overlook” of a kettle on the trail. I saw the sign for it, but I didn’t see tracks or even hints of tracks, and I wasn’t willing to veer off course and risk getting lost in the woods. But that was ok. For every trail you experience for the first time, it’s nice to leave at least one thing undiscovered, as an incentive to go back soon.

After that overlook, you’re going downhill for a long time….and you’re feeling that pit in your stomach saying “Yikes, every step downward means a step upward in the future!”

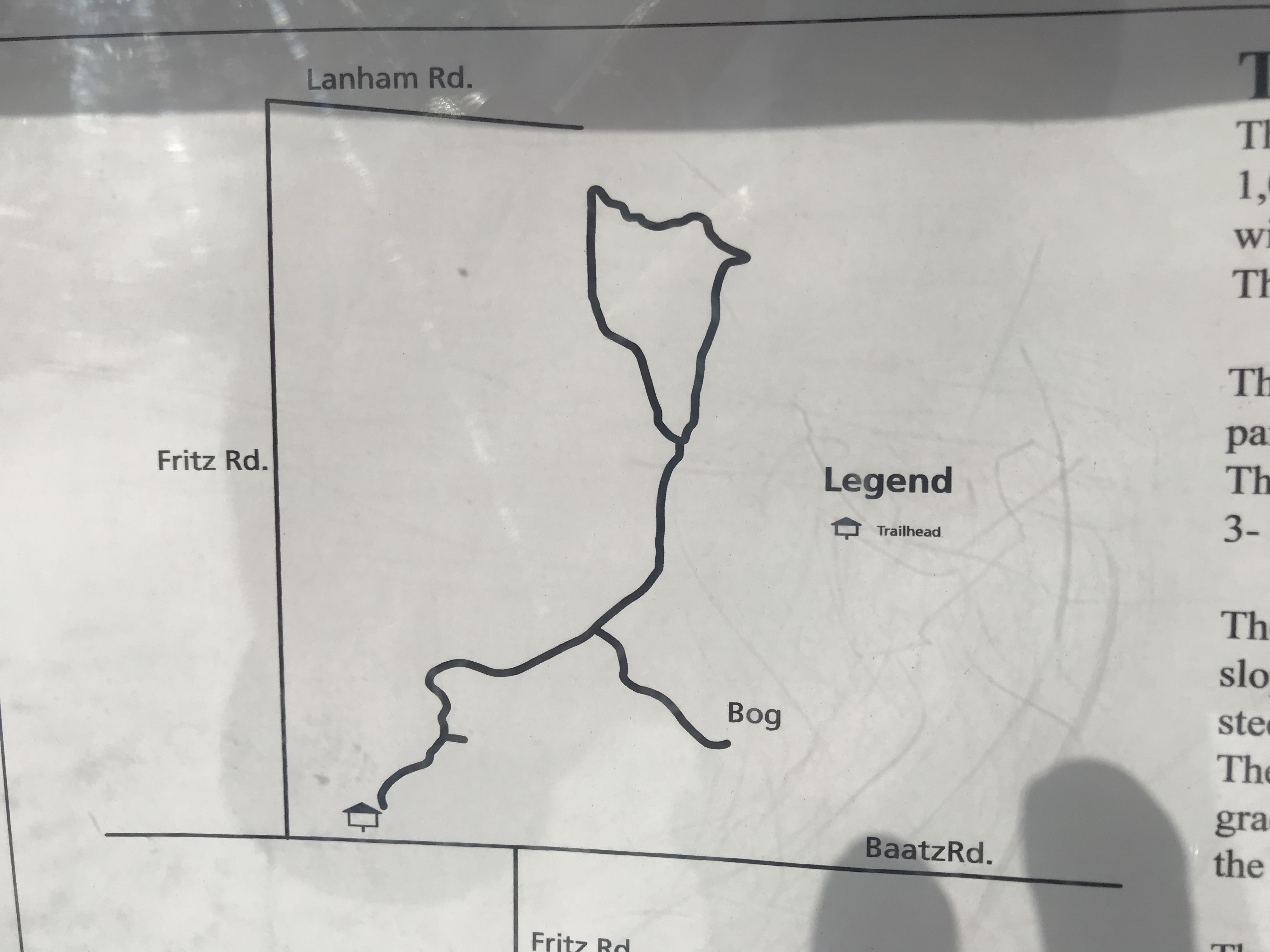

The trail is shaped like a lasso. There’s a loop at the end. Halfway toward the loop is a right turn leading to a kettle bog. After visiting the bog, you’ll have to double-back and reconnect with the main trail.

The trail is shaped like a lasso. There’s a loop at the end. Halfway toward the loop is a right turn leading to a kettle bog. After visiting the bog, you’ll have to double-back and reconnect with the main trail.

On this frigid February day, I was amused by the sign saying “Bog,” because I associate bogs with warmth, wetness, fecundity, and abundant plant and animal life. I took that right turn and headed down toward the frozen bog.

That bog has a spiritual energy. And once you reach it, the whole trail justifies itself, and you start to understand why this property was added to the National Lakeshore in the 1980’s. I’ve seen many little lakes in Michigan. But a kettle has a unique look — sunken in the landscape, as though formed by a meteor. I could’ve walked out on the frozen surface of the bog, amongst the drowned trees piercing skyward. But the human tracks stopped at the bog’s edge. And I felt a sense of risk-aversion…or was it superstition? If other hikers decided not to venture out onto the bog, for reasons of safety or perhaps spiritual reverence(?), then I should probably hang back too.

I headed back to the main trail and continued downhill toward the loop — again, with that sinking feeling that the uphill trek back was going to be a real workout. The loop takes you around another kettle hole. You hike up to the “rim” of the “crater,” and then around it. And the whole time you’re glimpsing through the trees at the hole below. I kept thinking of how magical this trail must be in spring. It’s apparently a wildflower hotspot. I imagined descending down into the kettle, into a fairlyland of orchids and frogs and a cornucopia of life. The spring, the future, will be here in about two months, and then we’ll be in the world of the present, a world of life, like the teeming Atlantic waters I grew up visiting. But now in the real present, it’s winter, and we’re still feeling like we’re on the surface of the moon, with the awesome past of Leelanau’s glacial activity inspiring awe and contemplation.

I headed back to the main trail and continued downhill toward the loop — again, with that sinking feeling that the uphill trek back was going to be a real workout. The loop takes you around another kettle hole. You hike up to the “rim” of the “crater,” and then around it. And the whole time you’re glimpsing through the trees at the hole below. I kept thinking of how magical this trail must be in spring. It’s apparently a wildflower hotspot. I imagined descending down into the kettle, into a fairlyland of orchids and frogs and a cornucopia of life. The spring, the future, will be here in about two months, and then we’ll be in the world of the present, a world of life, like the teeming Atlantic waters I grew up visiting. But now in the real present, it’s winter, and we’re still feeling like we’re on the surface of the moon, with the awesome past of Leelanau’s glacial activity inspiring awe and contemplation.

After finishing the loop, I was dreading the uphill return a bit. But I think I was so lost in thought, and impressed by what I’d seen, that the trek flew by in what seemed like a few minutes. When the sun is shining and snowshoeing conditions are excellent, it’s hard to begrudge a vigorous climb. And then you finally get back to your car, and you take off your sweaty layers, and you feel like a million bucks. And as you’re driving to your next destination, you’re reflecting on your experience. And you’re fantasizing about the past, the present, and the future. And you’re dreaming about a springtime visit to the Kettles Trail.